Comparing Apples to Oranges? Paying Attention to Measurement in Reporting the Gender Gap in Election 2016

In April 2015, the Barbara Lee Family Foundation (BLFF) and the Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP) launched Presidential Gender Watch 2016, a project to track, analyze, and illuminate gender dynamics in the 2016 presidential election. With the help of expert scholars and practitioners, Presidential Gender Watch worked for 21 months to further public understanding of how gender influences candidate strategy, voter engagement and expectations, media coverage, and electoral outcomes in campaigns for the nation’s highest executive office. The blog below was written for Presidential Gender Watch 2016, as part of our collective effort to raise questions, suggest answers, and complicate popular discussions about gender’s role in the presidential race.

In April 2015, the Barbara Lee Family Foundation (BLFF) and the Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP) launched Presidential Gender Watch 2016, a project to track, analyze, and illuminate gender dynamics in the 2016 presidential election. With the help of expert scholars and practitioners, Presidential Gender Watch worked for 21 months to further public understanding of how gender influences candidate strategy, voter engagement and expectations, media coverage, and electoral outcomes in campaigns for the nation’s highest executive office. The blog below was written for Presidential Gender Watch 2016, as part of our collective effort to raise questions, suggest answers, and complicate popular discussions about gender’s role in the presidential race.

Last week, FiveThirtyEight founder, and editor and chief Nate Silver shared images of an electoral college forecast if only women were to vote in the 2016 general election, based on the most recent polling data. This forecast showed Hillary Clinton defeating Donald Trump in a landslide (458 electoral votes, to Trump’s 80).

Here's what the map would look line if only women voted: https://t.co/sjVY67qouE pic.twitter.com/rrc3GuXmGl

— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) October 11, 2016

However, in a follow up tweet, Silver showed that if only men were to vote in the race, Donald Trump would easily win (350 electoral votes, to Clinton’s 188).

And here's if just dudes voted. pic.twitter.com/HjqJzIVwc4

— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) October 11, 2016

These images reflect the stark difference between men and women in their support for the 2016 presidential nominees. Difference in support between men and women for presidential candidates has been well documented over the past several decades, and is referred to as the gender gap in academic scholarship on this topic.

Silver’s statistics back expectations held by many pundits, social scientists, and the general public that on November 8 we will see a gender gap like none we have witnessed in American history. While partisanship is the primary fuel for the gender gap, some believe that the distinctly gendered environment of Election 2016 may further divide men and women’s votes. This speculation is driven by the fact that Hillary Clinton is the first female nominee by a major political party in our history, and has been revitalized in the wake of the widely covered video footage of Donald Trump on an Access Hollywood bus casually discussing sexual assault, and the now dozens of women alleging he made unwanted sexual advances. Given the #Trumptapes, and the numerous assault accusations, the question on many journalists’ and political observers’ minds is whether men and women will abandon Trump to a similar degree as a response, or if women will take particular offense, leading to an especially wide gender gap. In sum, will the gender gap in men and women’s vote presidential vote choice reach new heights in 2016?

Unfortunately, the gender gap is often misreported, or inconsistently calculated, complicating comparisons to past elections and making interpretation of differences between men and women as voters difficult. The different reporting of the gender gap also risks sowing confusion amongst the general public. So, what is meant by a “gender gap” and how it is measured? Our ability to determine whether the 2016 gender gap is unprecedented depends upon clear answers to these questions. Here, I review the meaning and measurement of the gender gap, and compare this measure to the myriad ways in which news media outlets have reported on it.

What is the Gender Gap?

The gender gap in voting is the difference in support between men and women for a particular candidate, typically the leading or winning candidate. Even when men and women favor the same candidate, they may do so by different margins, resulting in a gender gap. As described in this helpful explainer from the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University, the gender gap is calculated like this:

[%Women for Leading Candidate] – [%Men for Leading Candidate] = Gender Gap

This calculation captures the difference in support between men and women for the same candidate, and has been used for nearly four decades. Ellie Smeal, president and co-founder of the Feminist Majority Foundation, is credited with coining the term “gender gap” after the 1980 election (when she served as president of NOW), when 46 percent of women and 54 percent of men – based on exit polls – voted for Ronald Reagan. The 8 point gender gap in that race signaled a key, and now persistent, difference in women and men’s presidential preferences, and thus a tool for feminist organizers to gain leverage with political candidates and parties. The gender gap has ranged between 4 and 11 points in each presidential election since 1980, with women voters always more likely than men to support the Democratic candidate and less likely than men to support Republicans. In 2012, Democratic nominee Barack Obama won the election with support from 55 percent of women, and only 45 percent of men. This is a 10 point gender gap.

Some media have, and continue, to adhere to this measure of the gender gap. However, others in the news media, including some polling operations, report the gender gap as the distance between the advantage one candidate has among men and the advantage that candidate has among women. To calculate the advantage a candidate has among men/women, subtract the percentage of support they received from men/women from their opponent’s support from men/women. Using the 2012 election as an example, Obama’s advantage among men was -7 (45 percent of male voters minus Romney’s 52 percent of male voters), and his advantage among women was +11 (55 percent of female voters minus Romney’s 44 percent of female voters). The distance between these is 18 points. If you attempt to search online for the 2012 gender gap, you’ll find many reports noting the 18 point gap (for example, here, here, here), and not the 10 point gap, with a few exceptions such as Pew Research, and The New Yorker. To further confuse matters, some rely upon a Gallup report of a 20 point gender gap, which was calculated using pre-election polling data, not exit polls.

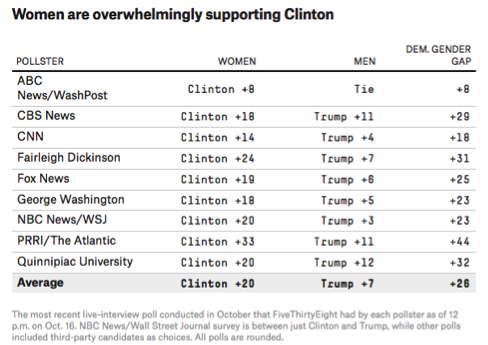

This same formula was used to calculate the expected 26 point gender gap for the 2016 presidential race, widely circulated earlier this week, from an article at FiveThirtyEight.com.

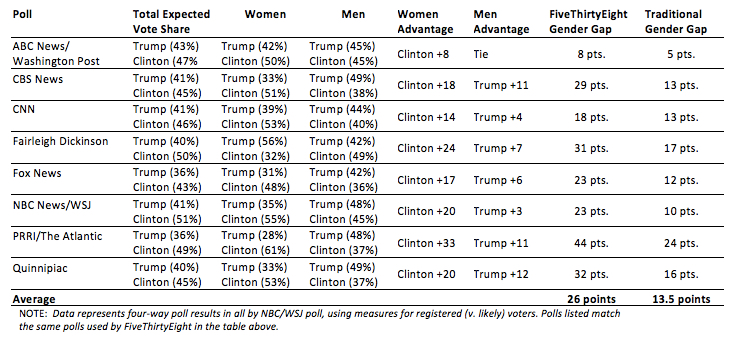

While these numbers as reported are not inaccurate, they are a less precise measure of the “gender gap” than originally intended. Most notably, they broaden the size of the gender gap and give greater weight to within-gender differences in vote choice than the between-gender differences that most starkly reveal the key role that men or women play in winning (or losing) an election for an individual candidate or party. To see these differences numerically, I recalculated the expected gender gap for the 2016 race for the same polls evaluated by FiveThirtyEight using the traditional measure in the table below.

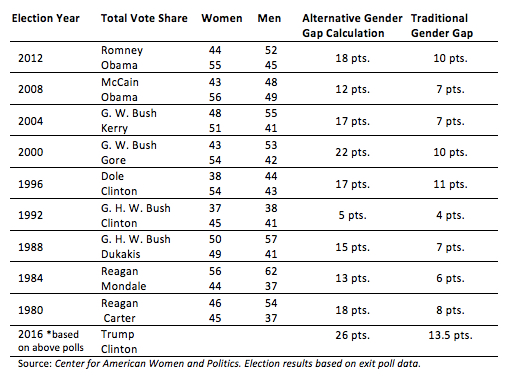

By this calculation, based on recent polls, I also expect a gender gap in 2016 that may well exceed previous presidential elections. The table below calculates gender gaps in presidential elections since 1980 using exit poll data, comparing the original calculation of the gender gap to the alternative calculation in recent reports.

The expected 13.5 point gender gap for 2016 would prove to be the largest gap since 1980, as political commentators and pundits have been speculating, driven both by women’s support for Clinton, and men’s support for Donald Trump.

Are these Different Calculations Meaningful?

Do the different calculations lead to different interpretations of our political reality?

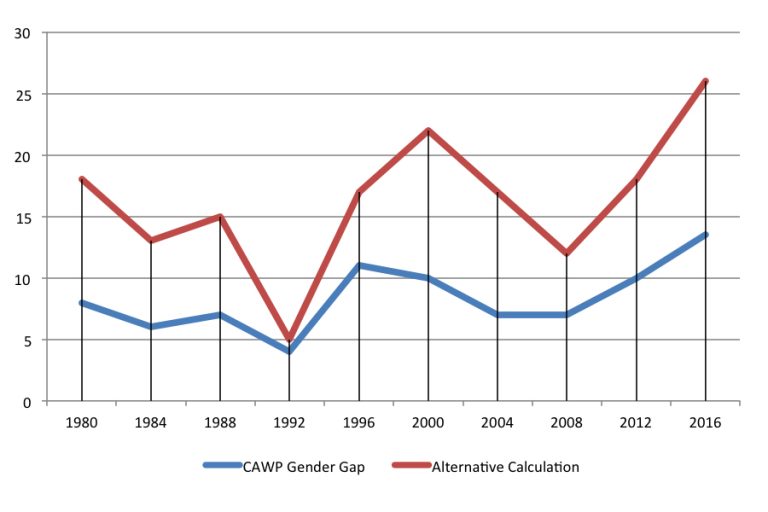

As displayed in the line chart above, for both calculations the relative degree of change from election to election is quite similar with the exception of 2004 to 2008, and 1992. The traditional calculation reported by CAWP and others shows a persistent gender gap for 2004 and 2008, while the alternative calculation suggests the gap was smaller in 2008 than in 2004. The alternative calculation captures the wider gap among male voters in 2004 (+14 points for Bush) versus 2008 (+1 point for Obama), demonstrating how this approach to measurement is more vulnerable to within-gender “gaps” for the major party candidates than the gap between men and women for the winning candidate, as originally intended. Similar vulnerability is why the 1992 measure is more volatile according to the alternative calculations. This smaller gap reflects that Clinton won support from both women and men but my small margins (Clinton won women by 8 points, and also men, by 3 points); this alternative measure reflects within gender gaps, and not just the gap between men and women.

The biggest difference between these calculations is simply that the alternative presents simply larger differences between men’s and women’s choices. Arguably, so long as the numbers that are being compared are calculated in the same manner and with the same data over time, then the trends will be accurately reported. But the inconsistency in calculation is not always noted in public reporting that summarizes data, yielding comparison of apples (the traditional measure) to oranges (the alternative calculation), As political reporting and academic scholarship both move toward more transparency in data collection and analysis, it would be ideal to establish greater consensus on how to discuss and calculate the gender gap to avoid confusion and misinformation, and ensure accuracy. In the meantime, however, the responsibility lays on those reporting the gender gap to make their calculation and data clear and on those consuming the information to make note of these factors in determining if the 2016 presidential race will really yield the gender gulf that is currently being described.

Kelly Dittmar and Christina Wolbrecht contributed to this post.