Much ink has been spilled about the role of gender equality and the #MeToo as a motivating factor for women in the 2018 midterm elections. The women’s movement, and opposition to Trump, is largely responsible for the record number of women running for office this year; the assumption, then, is that concerns about gender equality will also drive women to the polls. My own analysis shows that the issue appears to motivate Democratic women (and Democratic men to a slightly lesser extent) but fails to elicit much enthusiasm for other voters, particularly Republican women (and men).

However, while gendered issues are taking a much higher profile this election season, how do such concerns (or lack thereof among some women) rank compared with other issues? In other words, what issues are women voters prioritizing this campaign season? Do men and women have the same priorities? And how does this play into the midterm vote?

In a June 2018 national, online survey of 1,100 Americans using Qualtrics Panels, I asked Americans to indicate whether a range of issues was of critical important to them personally, one among many important issues or not that important of an issue.

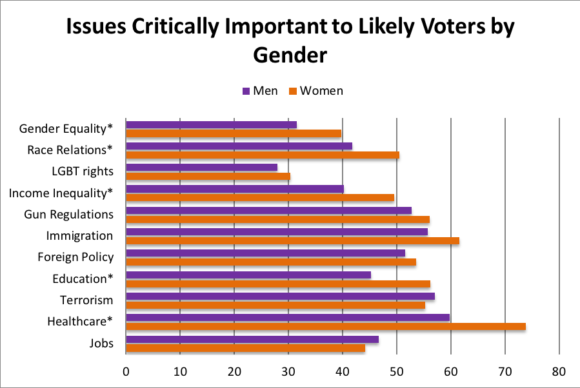

Source: Deckman/Qualtrics Survey June 2018

Note: Data include likely voters only and are weighted to match the U.S. population in terms of sex, age, race, education and income. (N=636)

Among likely voters —those Americans who said they are absolutely certain to vote come November, concerns about gender equality take a back seat to many other issues for both men and women. Roughly 4 in 10 women say gender equality is a critical issue of importance to them, compared with just 32 percent of men, a difference that is statistically significant at the bivariate level.

However, both women (74 percent) and men (60 percent) are far more likely to say that say health care is critically important to them (again a difference that is statistically significant)—the issue most likely to be identified by all likely voters as important. Save for LGBT rights, gender equality is less likely to be identified as a critical issue than ten others that range the gambit from guns, education, terrorism, foreign policy, immigration, and guns.

In addition to health care, voters are also prioritizing immigration, gun regulations, and foreign policy this election cycle. On six of the issues I asked voters about, there are no discernible gender differences, but women are more likely than men to express more concern about not only health care and gender equality, but also income inequality, race relations, and education. These differences should not be too surprising, given previous research shows that women are more likely to be supportive of more government spending on social welfare programs.

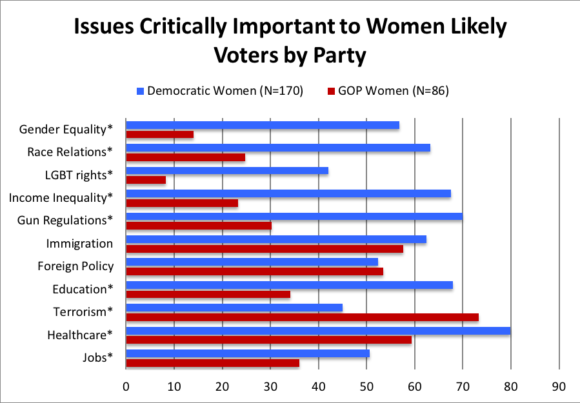

Of course, it is important to bear in mind that not all women share similar issue priorities, and party plays an important delineating role in helping to shape such concerns. The results with respect to Republican women should be viewed with some caution because of their smaller number among all survey respondents, but the trends are really revealing.

Source: Deckman/Qualtrics Survey June 2018

Note: Independent leaners are counted as partisans in reported data. Data include likely voters only.

Except for immigration and foreign policy, Democratic and GOP women likely voters prioritize much different concerns. For instance, Democratic women voters are far more likely to prioritize gender equality, race relations, income inequality, LGBT rights, gun regulations, health care and jobs as critically important to them compared with GOP women voters—and in many cases these issue prioritizations elicit very stark differences

By contrast, GOP women are more likely to say that terrorism is an issue that is critically important to them. Notably, however, majorities of GOP women also say health care, immigration, and foreign policy are important as well. (Although not reported here, Democratic men and Republican men also report distinct issue positions on all of these issues, except when it comes to jobs.)

Recent analyses of campaign ads and websites make clear that primary candidates from both parties are attuned to these priorities. They are stressing issues that appeal to their base of likely voters, including women, no doubt in an effort to motivate them to come to the polls. For instance, Democratic candidates seeking their party’s nomination in congressional races are most likely to discuss health care and social issues in their campaign ads, in addition to running directly against Donald Trump. Many Republican candidates are not only embracing Trump as a way to appeal to the base in advertising, but they are hitting immigration issues and taxes hard in their own ads. Democrats are also likely to stress gun regulations and education as well in their campaign websites, but health care continues to dominate as the most frequently discussed issue.

This strategy to mobilize each party’s voter base might be a smart one, according to political scientist Rachel Bitecofer: she argues that in our hyper-partisan, nationalized environment, control of Congress may rest on the backlash from negative partisanship. Just as Republicans picked up untold numbers of legislative seats in 2010 in response to the election of Barack Obama, and complacent Democratic voters underperformed in terms of turnout compared with angry Republican voters in 2014, she predicts a large blue wave come November.

Women voters will likely play an outsized role in this predicted wave for several reasons. First, current generic-ballot House are estimating that women voters may vote more Democratic than men in House elections by nearly 25 percent. Second, women tend to turn out to vote at higher rates than men in elections, even during recent midterm elections. Third, in terms of sheer numbers, women voters are far more likely to identify as Democrats than Republicans. My data here only reinforce that point: when independent leaners are considered as partisans, my national survey finds that, among women likely voters, there are more than twice as many Democrats as Republicans.

Does this mean that Democratic candidates should embrace the very progressive ideas in their campaigns, such as universal health care, a jobs guarantee program, or free college tuition, that have been touted by the Bernie Sanders wing of the party, as a way to connect with women voters? As with much in politics, it depends on location. This overtly progressive message helped Democrats such as Alexandra Ocario-Cortez and Rashida Tlaib win their primaries, but they did so in heavily Democratic districts. Running on such policies won’t necessarily help Democratic candidates in districts that are toss-ups. While majorities of likely Democratic women voters may respond well to such policies, there are still plenty of Republican women who may not—not to mention Democratic and Republican men.

As campaigns enter the home stretch in election 2018, these data serves as an important reminder to candidates and political observers that women voters are not monolithic and that the issues they care most about are diverse and multi-faceted. In the midterm elections, giving women voters what they want will take more than a hashtag.

From March to December 2018, the

From March to December 2018, the