What Does Buttigieg’s Success Mean for Gender Progress in American Politics?

Final results from the Iowa Democratic Caucus are still trickling in but one takeaway is clear: openly-gay former mayor Pete Buttigieg did quite well, exceeding expectations, helping his chances of becoming the 2020 Democratic nominee. So did Senator Bernie Sanders. Despite strong performances in Iowa, however, Senators Elizabeth Warren and Amy Klobuchar remain outside of the top-two contenders heading into New Hampshire’s presidential primary.

After the nomination of the first woman for president in 2016 and record-level electoral victories of Democratic women across levels of office in 2018, what does it mean that a gay White male mayor of the 305th largest American city has had more electoral success than the four women senators who entered the 2020 presidential contest with a combined 37 years of senatorial experience?

Would Patricia Buttigieg and Berniece Sanders, with identical levels of political experience and talent, be doing as well in 2020? Would a lesbian with Buttigieg’s record and campaign style be as warmly embraced by American voters? Would a Black woman with Obama’s message and charisma have won the 2008 Iowa caucuses? History suggests the answer to this question is no, especially for candidates with intersectional identities such as a lesbian or Black woman. Even White women, however, are struggling to be seen as electable.

While out LGBTQ individuals are still less than 2%, and women are less than 30%, of officeholders at the statewide, state legislative, and congressional levels, women and LGBTQ candidates have enjoyed record electoral success in recent years. Consistent with the surge in women’s political involvement since Trump’s election in 2016, record numbers of women ran for and won elected office in 2018 and gains continued into 2019. The last four years have also seen an explosion in the candidacies and elections of openly LGBTQ candidates, especially of gay White men. According to the Victory Fund, as of February 2020, there are 841 openly-LGBTQ elected officials nationwide. This figure is a huge increase from their first report in October 2017, when only 448 openly-LGBTQ officials were serving. This is happening not just in traditionally-Democratic areas but also in areas with more mixed partisanship like Kansas and Colorado, which elected the first openly-gay man as governor in 2018.

Public opinion suggests this success should extend to the presidential arena. The public regularly voices its openness to voting for a woman for president, including 94% of respondents in a May 2019 Gallup poll. The same survey showed that 76% of Americans would vote for a gay or lesbian candidate. While that number is three times the level of support that Gallup found when they first asked the question in 1978, it is far lower than support for a female presidential candidate.

An Ipsos/Daily Beast poll from June 2019 found that 74% of Democrats and Independents were comfortable with a female president. However, a common proxy for soliciting attitudes that individuals may be reluctant to admit is to ask what they assume their neighbors’ beliefs may be. When asked that question, only 33% thought their neighbors would be comfortable with a female president. The poll didn’t ask the same question about comfort voting for a gay candidate but in head-to-head matchups, only 61% of Democratic respondents said they would vote for Buttigieg over Trump compared to 78% for Warren.

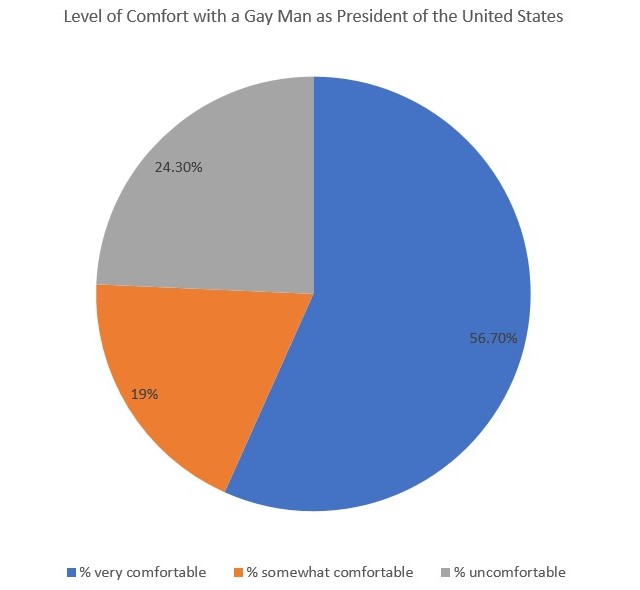

We conducted a national survey of 1,200 U.S. adults in 2019 to gauge levels of comfort with members of various LGBTQ identities in different contexts, including as President of the United States. Only 56.7% reported they were very comfortable with the idea of a gay male president, and another 19% said they were somewhat comfortable for a total of 75.7%, mirroring the results of the Gallup poll. While this might seem like a high proportion, it means that nearly 1 in 4 respondents was uncomfortable with the idea, a large number for a tightly contested race.

Note: N=1,183, Data collected Feb. 8-March 5, 2019. Source: Michelson and Harrison 2020

Our survey also collected data on levels of comfort with lesbians, bisexual men and women, and transgender men and women as President of the United States. Overall, the discomfort that members of the public report toward gay men being president is similar to their comfort with lesbians and bisexuals. Respondents reported slightly higher levels of comfort with lesbians (59.1% very comfortable, 76.3% comfortable overall) and bisexual women (59.2% very comfortable, 76.1% comfortable overall); there was, however, slightly lower levels of comfort with bisexual men (56% very comfortable, 73.7% comfortable overall).

Comfort was significantly lower, however, when we asked about transgender people serving as president. Only 42% of respondents said they were very comfortable with a transgender man as president (58.1% comfort overall) and 42.5% said they were very comfortable with a transgender woman as president (57.8% comfort overall).

When it comes to electability, electoral outcomes are the only metrics that matter, so what do we make of these poll numbers given the actual Iowa results? That the public knows they should not voice their misogyny but they are not quite there on homophobia? That their homophobia is weaker than their misogyny and they are more willing to vote for a gay man? Does this mean that survey evidence of the willingness of voters to support a woman is just cheap talk? This could simply be further evidence that when surveys ask questions in generalities, responses don’t perfectly translate to voters’ actual opinions about specific, multifaceted candidates.

Another potential answer to these questions involves media coverage. In comparison to the media coverage of the historic nature of Hillary Clinton’s candidacy as a woman, comparatively less attention has been paid to Buttigieg’s sexual orientation. Perceptions of his electability might decrease if there is more coverage of voters who may see his identity as threatening and scary. For example, after the Iowa caucuses, a video emerged of a woman who wanted to revoke her vote for Buttigieg after realizing he was gay.

If Buttigieg prevails, his nomination will be historic. Whether the nomination will translate into victory in the general election is unclear, but his successes so far are already paving the way for more openly LGBTQ candidates to run for office, including the presidency, in future cycles. This is surely something to be celebrated.

At the same time, that another man will likely win the nomination delays yet again the possibility of America electing its first woman president. Hillary Clinton—arguably more well qualified and certainly more experienced—was put aside for a Black man in 2008. Will Elizabeth Warren and Amy Klobuchar—both arguably more experienced—be passed over by the party for another man?

Several women are widely viewed as leading contenders for the vice presidency slot (cough, Stacey Abrams, cough). However, every previous successful candidate for the presidency and vice presidency has been a man. America has made great strides over the past century on gay rights and women’s rights but in many ways, the American presidency remains an old, White, cisgender boys’ club.

Harvey Milk said in a 1977 speech, “It's not my victory, it's yours and yours and yours. If a gay can win, it means there is hope that the system can work for all minorities if we fight.” Buttigieg has certainly given LGBTQ people hope. The day after the Iowa caucuses, Buttigieg gave an emotional speech, saying, “It validates for a kid, somewhere in a community, wondering if he belongs, or she belongs, or they belong in their own family, that if you believe in yourself and your country, there’s a lot backing up that belief.”

As for women? On the centennial of the 19th amendment, women are still waiting for an equal chance at the White House.