Ahead of today’s primary in Maine, Gender Watch 2018 asked Cynthia Terrell, Director of RepresentWomen, to share her expertise on ranked choice voting and its potentially gendered effects on the electoral process and outcomes.

This week, Maine makes history as the first state to use ranked choice voting (RCV) in their statewide and federal elections. How does RCV work in Maine?

In a ranked choice voting election voters have the option to rank candidates in order of preference: 1st choice, 2nd choice, 3rd choice and so on. If a candidate gets over half of all the first choices, that candidate wins. If no candidates gets over 50%, the candidate with the fewest votes is defeated, and those who ranked that candidate as “number 1” now have their ballots go to their next choice. This process of eliminating the last-place candidate and having their votes go their next choice continues until a candidate wins with more than half the votes.

Nearly every voter in Maine will experience use of RCV in a primary contest.

Some cities with RCV get results on election night. In Maine, election officials only will report first choice outcomes. To win on election night, you must have a majority of the vote.

Voters will vote on whether to retain RCV at the same time as voting with the system.

In what ways, if any, is RCV good for women candidates? Are these potential benefits distinct to women, or the same for men

Studies show ranked choice voting increases the civility of campaigns and reduces negative attacks. Rather than engage in mudslinging, candidates in RCV elections reach out to supporters of their opponents to earn second or third choice spots on those voters’ ballots. Women candidates often prefer running on a positive message. Such civil campaigns reward grassroots organizing over expensive negative advertising, putting victory within reach of less well-funded candidates.

By giving voters backup choices, ranked choice voting allows everyone to support their true favorite candidate without throwing their vote away. This also means candidates can run without concern about unfairly undermining, or conversely being harmed by, another candidate with similar views or a shared base of support. Multiple women candidates can run under RCV without hurting each other’s chances, and voters are freed to support women candidates without fear they will split the vote. Qualitative interviews with women who have run in ranked choice voting elections confirm that the anticipated civility of the campaign process led them to decide to run.

To recap:

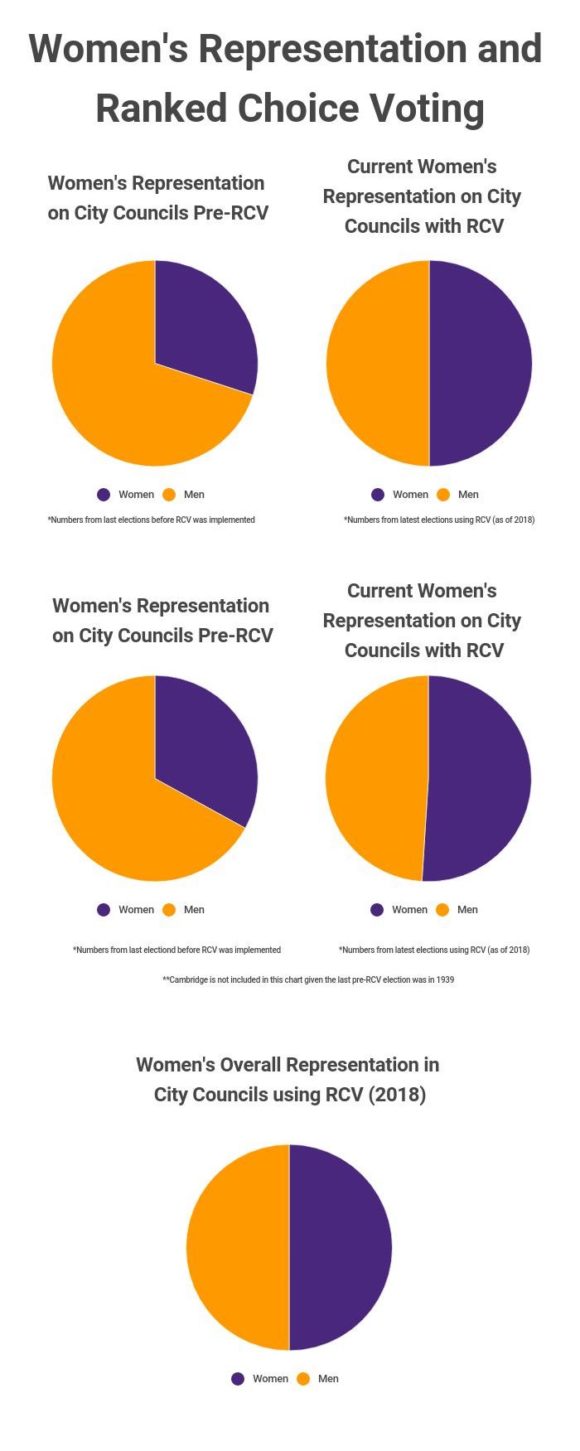

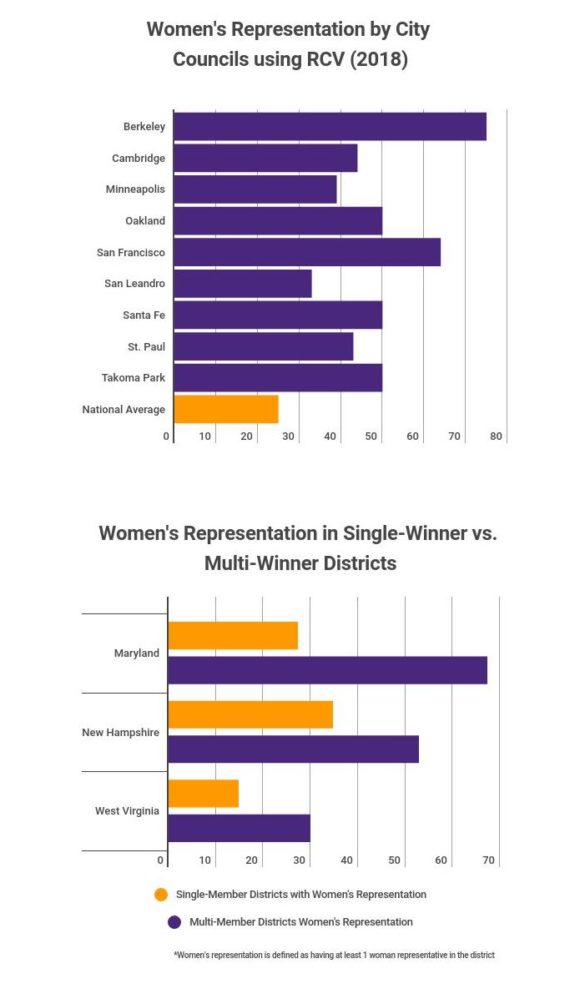

The data from the municipalities that use RCV shows that women are being elected at about twice the rate as the norm but of course there are all sorts of variables.

Elections in jurisdictions with RCV have common themes:

- elections are known to be more civil so more women candidates, who tend to be risk averse, consider entering race

- often primary and general elections are collapsed into one rcv election which makes running more affordable for first time candidates,

- the incentive for candidates to be civil during the campaign (as they seek support from their opponents’ supporters) leads to more grassroots outreach and focus on issues that plays to women candidates’ strengths,

- positive campaigns cost less which is an advantage for many women candidates

- turnout is above national average in RCV cities creating a virtuous cycle for voters and candidates who are all more engaged in process

- campaign outcomes are voter-driven which appeals to first time candidates establishing a political identity

Are there any examples within the U.S. where you’ve seen RCV contribute to women’s electoral success?

Women are twice as likely, on average, to be elected to office in a cities with ranked choice voting than the norm. There are over 75 colleges and universities that use ranked choice voting for their student government elections – while we haven’t tracked all the election outcomes, an informal survey confirmed that more women are running and winning than on non-RCV campuses.

Maine is a unique state in many ways, including the strength or third parties in the state and the support for electoral reforms like RCV. Do you see any other states moving toward RCV? When/how?

In 2016, Maine passed RCV with a ballot initiative with the second highest vote total in Maine history. The Maine Supreme Court advised that portions of the law violated the Maine state constitution. The state legislature ultimately voted to block it, but citizens used a ‘People’s Veto’ and petitioned for Tuesday’s vote on whether to keep RCV for its clearly legal uses. A “yes” vote on the People’s Veto is a vote in favor of keeping RCV for future primary elections and for the November elections for U.S. Senate and U.S. House.

Maine voters instituted ranked choice voting for a good reason. The winners of nine of Maine’s last 11 governors’ races were elected without a majority of votes. That dates back to the 1970s. The last three governors – a Democrat, a Republican and an independent – each won an election for governor with less than 40 percent. But many other Maine elections are not won with a majority. Indeed, it is quite possibly that all four primaries with more than two candidates will not be won in the first round, but will rely on RCV to uphold majority rule.

In addition to the state of Maine, this system is used by a growing number of American cities, including San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley, Minneapolis, St. Paul, Minnesota; Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Portland, Maine – for two mayoral elections in Portland, where more than 70% of voters approved RCV in the 2016 measure. This year, three new cities have voted to move to RCV, mostly recently in New Mexico’s second largest city, Las Cruces.

Ranked choice voting is not a partisan issue. In Maine, RCV has become a more partisan issue that is the norm. For example, when Utah’s House of Representatives passed RCV for elections for Congress and president last year, the vote was backed heavily by members of both major parties. When Utah approved a new law this year to enable cities to use RCV, there were only three dissenting votes in the entire legislature.

There are now FairVote organizations on the ground in over 20 states. Ranked choice legislation was introduced in over 30 states in 2017/2018 and is being considered in a number of cities including New York City this year.

Your organization has advocated for ranked choice legislation. Why do you think this type of electoral reform is important for women’s political representation?

I believe there is value in making these systems reforms because they accelerate the pace of change and get more women into office quickly building the capacity for other reforms that must happen to achieve equality and help to transform voter opinion about women’s ability to lead.

From March to December 2018, the

From March to December 2018, the