The Power of Black Women’s Votes in Presidential Politics

In April 2015, the Barbara Lee Family Foundation (BLFF) and the Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP) launched Presidential Gender Watch 2016, a project to track, analyze, and illuminate gender dynamics in the 2016 presidential election. With the help of expert scholars and practitioners, Presidential Gender Watch worked for 21 months to further public understanding of how gender influences candidate strategy, voter engagement and expectations, media coverage, and electoral outcomes in campaigns for the nation’s highest executive office. The blog below was written for Presidential Gender Watch 2016, as part of our collective effort to raise questions, suggest answers, and complicate popular discussions about gender’s role in the presidential race.

In April 2015, the Barbara Lee Family Foundation (BLFF) and the Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP) launched Presidential Gender Watch 2016, a project to track, analyze, and illuminate gender dynamics in the 2016 presidential election. With the help of expert scholars and practitioners, Presidential Gender Watch worked for 21 months to further public understanding of how gender influences candidate strategy, voter engagement and expectations, media coverage, and electoral outcomes in campaigns for the nation’s highest executive office. The blog below was written for Presidential Gender Watch 2016, as part of our collective effort to raise questions, suggest answers, and complicate popular discussions about gender’s role in the presidential race.

Recent debates over the racial dynamics of the Democratic primary have included specific focus on the Democratic candidates’ support from and accountability to Black voters. When Professor Michael Eric Dyson wrote “Yes She Can” about Clinton’s ability to “do more for Black people than Barack Obama,” he sparked a discussion about how attentive the Democratic frontrunner has been and will be to the interests of and concerns of the Black community. But Clinton’s ability to implement policy is dependent on winning, and winning requires her to secure and mobilize the Democratic base – of which Black voters are a significant part.

Multiple analyses have demonstrated Clinton’s lead among Black voters, but columnists and commentators rightfully question whether electoral support equals the enthusiasm necessary to match Black turnout in 2008 and 2012. Some have also sought to challenge claims that Clinton’s support among Black voters is in any way automatic, including Raina Lipsitz, who argues that “Clinton is not entitled to Black votes.” Complicating the narrative around Black voters is essential to painting a clearer picture of the presidential landscape in 2016. That means telling a more complex story about Black voters’ candidate preferences and policy priorities and, in doing so, recognizing the gender differences among Black voters.

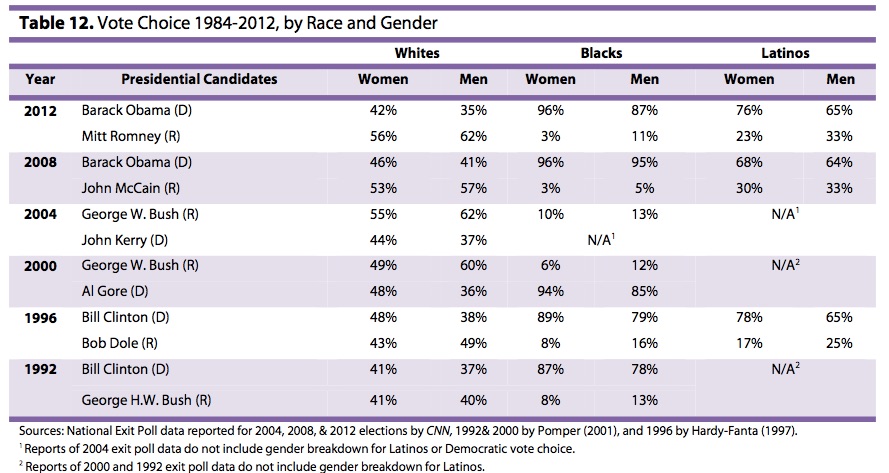

In a new report (Voices. Votes. Leadership. The Status of Black Women in American Politics) from Higher Heights, I detail the important role that Black women voters will play in the 2016 election. In both 2008 and 2012, Black women voted at a higher rate than all other race/gender subgroups for the first time in U.S. history. Moreover, they proved to be the most reliable Democratic voters, with 96% of Black women voting for President Obama in both election years. Black women have also registered and voted at higher rates than their male counterparts in every election since 1998. While all Black voters have voted overwhelmingly Democratic in each election year, a gender gap still emerges in each presidential contest since 1992, with an even greater proportion of Black women supporting the Democratic candidate.

Black women also represent a significant portion of the Rising American Electorate (RAE), an estimated 125 million eligible voters including unmarried women, people of color, and people under 30. Black women sit at the intersection of these groups, representing just over half of the 27.9 million eligible Black voters and 19% of all eligible unmarried women voters. They also represent the most active and dependable contingent of the RAE, contributing to its growing influence and playing an essential role in building coalitions across RAE groups to influence electoral outcomes in future races.

So what do we learn about the 2016 presidential race from the data? As Joan Walsh recently wrote, “What is clear is that, in order to win the White House and make inroads into the Republican majorities in Congress, the Democratic Party will need black voters to turn out in high numbers—and they’ll need black women in particular.” That need demonstrates the power of Black women’s votes in 2016, power that – if recognized and harnessed by Black women – can be leveraged to make policy demands on Democratic candidates. That leveraging will require Democratic candidates – and Republican candidates seeking Black women’s votes – to address the policy problems confronting Black women, such as those detailed in the most recent survey conducted by Essence and Black Women’s roundtable. Moreover, it means recognizing the benefit of Black women’s electoral energy for mobilizing the votes of the broader community, as Higher Heights co-founder Glynda Carr argues when noting, “When you fire up a black woman to vote, she’ll be firing up her family and firing up everybody.”

Identifying the power and influence of Black women’s votes is important to challenging singular narratives of “the women’s vote” or “the Black vote” in 2016 (and beyond). Most importantly, doing so gives voice to Black women in the presidential election debates and discussions, and – as we discussed with Dr. Niambi Carter earlier this year – makes Black women visible in presidential politics.