Lesson 4: Win or lose, this year’s women candidates made history in multiple ways…and that’s worth celebrating.

In April 2015, the Barbara Lee Family Foundation (BLFF) and the Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP) launched Presidential Gender Watch 2016, a project to track, analyze, and illuminate gender dynamics in the 2016 presidential election. With the help of expert scholars and practitioners, Presidential Gender Watch worked for 21 months to further public understanding of how gender influences candidate strategy, voter engagement and expectations, media coverage, and electoral outcomes in campaigns for the nation’s highest executive office. The blog below was written for Presidential Gender Watch 2016, as part of our collective effort to raise questions, suggest answers, and complicate popular discussions about gender’s role in the presidential race.

In April 2015, the Barbara Lee Family Foundation (BLFF) and the Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP) launched Presidential Gender Watch 2016, a project to track, analyze, and illuminate gender dynamics in the 2016 presidential election. With the help of expert scholars and practitioners, Presidential Gender Watch worked for 21 months to further public understanding of how gender influences candidate strategy, voter engagement and expectations, media coverage, and electoral outcomes in campaigns for the nation’s highest executive office. The blog below was written for Presidential Gender Watch 2016, as part of our collective effort to raise questions, suggest answers, and complicate popular discussions about gender’s role in the presidential race.

One year ago, the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University and the Barbara Lee Family Foundation launched Presidential Gender Watch 2016, a nonpartisan project to track, analyze, and illuminate gender dynamics in the 2016 presidential election. The goal of the project was – and remains – to lend expert analysis to the dialogue around gender throughout the election season. With just over 200 days until Election Day, it’s worth taking stock of what we’ve been up to. Over the next week, we will post 5 key lessons learned. Today, we review lesson number four: Win or lose, this year’s women candidates made history in multiple ways…and that’s worth celebrating. (See hyperlinks for full analyses written over the past year.)

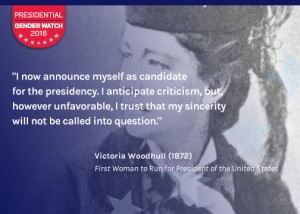

Amidst our efforts to emphasize the way in which gender matters for women and men engaged in presidential politics, we have not ignored the historic significance of women’s candidacies in 2016. Our very first post analyzed the 143 years in which women have run for president, as we also illustrated in our interactive timeline. When two women emerged as presidential contenders, we noted that this would be the first presidential campaign with women competing for both major parties’ nominations. Here’s some more historical context: from 1972 to 2012, 139 men and just 5 women competed in major party primaries for president. In 2016, Clinton and Fiorina added two more women to that list.

Of course, our celebration of these two women was a tempered one, as we watched 21 men throw their hats in the ring (and asked, “Why not another woman?”). The dominance of male contenders (and officeholders) plays into the gendered language we use in presidential contests, something student Colin Sheehan emphasized in his analysis of how and why pronouns matter when we talk about the presidency.

Altering that language requires recognizing women as real, viable presidential contenders. In 2016, few have questioned Hillary Clinton’s viability. Interestingly, that has led to relatively minimal attention to her historic achievements as the first (and only) woman to win presidential primaries in 33 states and territories (10 in 2016 thus far), including her win in the nation’s first contest in Iowa this year.

Beyond altering the image and language of the American presidency, women candidates also have the potential to disrupt the tactics and content of campaigns. In October 2015, we asked what difference it made to have two women in the race and noted one particular effect: we’re talking about feminism. Of course, the ways in which candidates talked about feminism varied. Carly Fiorina’s feminism included confronting the sexism she faced on the campaign trail, as we noted after she took on the ladies of The View. But Fiorina’s feminism was also hard to pin down, as she struggled with how to use, address, or embrace her gender throughout her presidential campaign. When she conceded, we wrote about this dissonance as evidence of both confusion and constraint.

Clinton’s campaign has faced fewer constraints in embracing gender as an electoral asset. She has described gender among the merits she would bring to the presidency, and has mainstreamed gender in her policy agenda and political rhetoric. While still subject to gendered expectations that privilege masculinity in the Oval Office, Clinton’s strategy in 2016 challenges some established rules of the game to expand the issues, expertise, experiences, and traits expected of presidential candidates. Her candidacy might disrupt our associations of presidential success with proving manliness so that presidential power can also derive from being a woman.