Gender Matters: A Status Check on the Gender Gap in Presidential Primaries

In April 2015, the Barbara Lee Family Foundation (BLFF) and the Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP) launched Presidential Gender Watch 2016, a project to track, analyze, and illuminate gender dynamics in the 2016 presidential election. With the help of expert scholars and practitioners, Presidential Gender Watch worked for 21 months to further public understanding of how gender influences candidate strategy, voter engagement and expectations, media coverage, and electoral outcomes in campaigns for the nation’s highest executive office. The blog below was written for Presidential Gender Watch 2016, as part of our collective effort to raise questions, suggest answers, and complicate popular discussions about gender’s role in the presidential race.

In April 2015, the Barbara Lee Family Foundation (BLFF) and the Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP) launched Presidential Gender Watch 2016, a project to track, analyze, and illuminate gender dynamics in the 2016 presidential election. With the help of expert scholars and practitioners, Presidential Gender Watch worked for 21 months to further public understanding of how gender influences candidate strategy, voter engagement and expectations, media coverage, and electoral outcomes in campaigns for the nation’s highest executive office. The blog below was written for Presidential Gender Watch 2016, as part of our collective effort to raise questions, suggest answers, and complicate popular discussions about gender’s role in the presidential race.

What is the gender gap?

Talking about gender is commonly misinterpreted as simply talking about women. As a result, reports about the gender gap in politics and polling often focus only on how women vote. The gender gap, however, is defined as the difference between the proportions of women and men who support a given candidate, generally the leading or winning candidate. It is the gap between the genders, not within a gender. For those who like equations, here it is:

[% Women for Leading or Winning Candidate] – [% Men for Leading or Winning Candidate] = Gender Gap

Why does it matter?

There has been a persistent gender gap in presidential voting since 1980, with women voters more likely to support Democratic candidates than men; likewise, men have been more likely to support Republican candidates than women. In every presidential election since 1988, the majority of all women voters have cast their ballots for the Democratic candidate. The majority of men have voted for Republican presidential candidates in all elections since 1980 except for 1992 and 2008, where majorities of men and women supported Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, respectively.

While gender differences in vote choice emerged before 1980, researchers Heather Ondercin and Jeffrey Bernstein date to 1980 the “dawning of a new gender gap” that many researchers attribute to the catalytic effect of Ronald Reagan’s policy agenda and presidential campaign. Susan Carroll writes: “It may have taken 60 years to arrive, but the women’s vote that the suffragists anticipated is now clearly evident and has been influencing the dynamics of presidential elections for almost three decades.”

The gender differences in candidate preferences have occurred at the same time that women have outpaced men in voter turnout; in every election since 1980, women voters have outnumbered and outvoted men. The dominance of women voters has made the gender gap in vote choice, and the policy concerns behind it, much harder for any candidate to ignore.

These gender dynamics matter for campaign strategy, influencing the ways in which candidates appeal to men and/or women voters, and the extent to which they try to build on areas of strength (potentially expanding the size of the gender gap) or compensate for perceived areas of weakness (trying to reduce the size of the gender gap) in trying to maximize their vote on Election Day.

But it’s more complicated.

Women – like men –are not a singular voting bloc. The diversity within gender groups is key to identifying winning strategies, but must also be interrogated in order to understand the sources and influence of the gender gap in presidential politics.

In general elections, we know that women of color – and black women especially – have fueled the gender gap, voting at the highest rates for Democratic presidential candidates in each contest since 1996; white women have been more likely to support Republican presidential candidates in the most recent elections. Researchers have similarly investigated differences across generation and marital status, demonstrating within-gender differences that fuel presidential preferences. Recognizing the intersections of gender with race and ethnicity, age, ideology, and marital status – among other important sites of diversity – reminds scholars and practitioners alike that no group of voters is monolithic.

Importantly, however, gender gaps have been persistent within these subgroups, with women still more likely than men to support a Democratic candidate, and men more likely than women to support a Republican.

What’s it looking like in 2016?

While research largely focuses on the presence and influence of the gender gap in general election races, especially at the presidential level, the 2016 election provides a site for investigating gender differences within party primaries. As Barbara Norrander has found, there were gender gaps evident in one-quarter of Democratic primary contests between 1980 and 2000, and in one-third of Republican primaries in the same period. Just as in a general election, significant gender differences in vote choice – along with gender differences in turnout – can make the difference in the most competitive races.

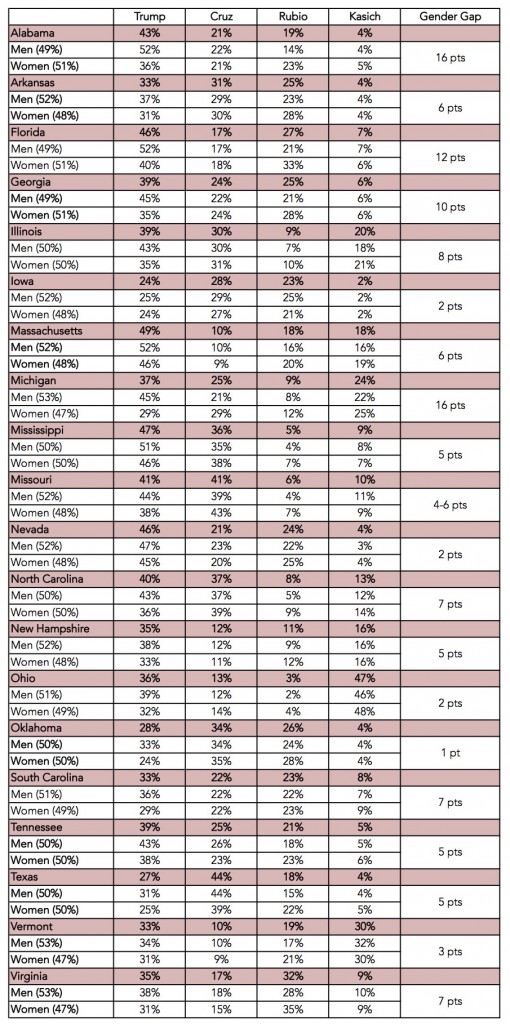

Republican Primaries

In the 20 Republican primaries and caucuses to date where exit/entrance polls are available, the average gender gap is 6.5 points. The largest gaps – of 16 points – came in Alabama and Michigan. In Alabama, Donald Trump won support from 52% of GOP men and just 36% of GOP women. However, he still won a plurality of women voters by a margin of 13 points over Marco Rubio. In Michigan, Trump earned votes from 45% of GOP men, but tied Ted Cruz with women – earning just 29% of their support. These differences are even more meaningful since men make up a larger proportion of the Republican primary electorate than women in most states.

In other states, the gender gap has been as low as one point in GOP primaries, as in Oklahoma, where Cruz won the contest with 34% of support among men and 35% support among women. Interestingly, the gender gap in Trump’s support there was nine points (33% of men, 24% of women); he finished second overall and third among women voters. Similarly, while the gender gap was only two points in Ohio’s GOP primary (46% men, 48% women supported Kasich), there was a larger gap (seven points) in Trump’s support. The other two contests with two-point gender gaps were Iowa and Nevada, both caucus states.

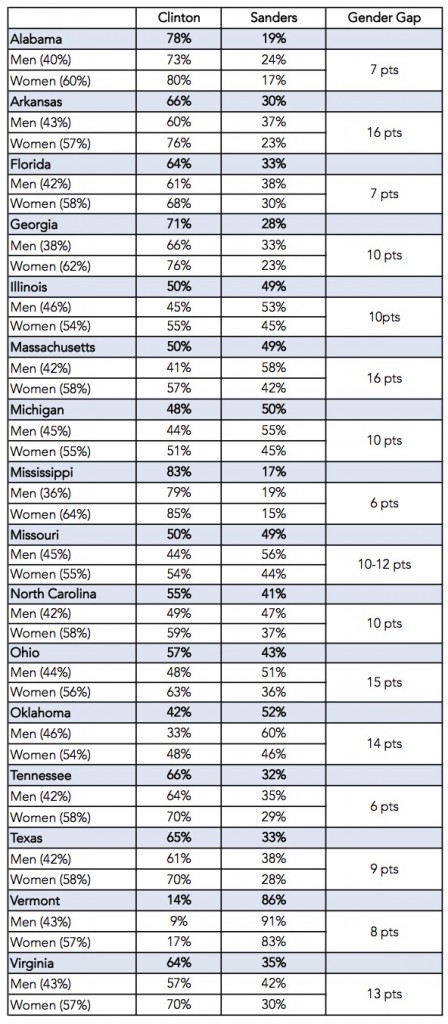

Democratic Primaries

The gender gaps in Democratic contests have been larger, on average, than those in the GOP primaries. In the 16 Democratic primaries and caucuses to date where exit/entrance polls are available, the average gender gap is 10.5 points. The smallest gaps have been six points, in Mississippi and Tennessee – where Hillary Clinton won by large margins. But gender gaps are evident in races where both Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders have won. There was a 16-point gender gap – the largest thus far – in Arkansas, where Clinton won the majority of men (60%), but won among women by an even larger margin (76%). The gap between men’s and women’s votes was the same in Massachusetts, where Clinton eked out a win overall with the help of women voters, who were a larger proportion of the Democratic primary electorate and among whom 57% cast ballots for Clinton.

Making the Difference in Tight Contests?

Massachusetts was not the only state where women may have made the difference in Democratic primary results. In all contests where the margin of victory was within three points, gender gaps of at least ten points occurred. Just this week, Clinton earned a slim victory in Illinois with the support of 55% of Democratic women and just 45% of Democratic men. In Missouri, where the results remain too close to call, Clinton might maintain the lead thanks to women, earning 54% of their support versus just 44% of men’s. In Michigan, where Sanders won by two points overall, Clinton’s advantage among women voters was just six points over Sanders, compared to a 10-15 point advantage among women in the other top competitive states.

There have only been four tight races on the Republican side. While gender differences do not appear to have tilted the balance in any candidate’s favor in Vermont or Iowa, Trump may have men to thank for eking out wins in Arkansas, and possibly Missouri. GOP women voters in Arkansas were nearly evenly split among the top three male candidates, while 37% of men – who made up 52% of the GOP primary electorate – supported Trump and 29% supported Cruz. In Missouri, where Trump and Cruz are currently tied, Trump won 44% of men’s support and 38% of support among GOP women; Cruz’s gender break mirrors Trump’s, with 39% of men and 43% of women casting ballots for him. Again, in a state where men make up a larger proportion of the GOP electorate, that difference – albeit slight – may determine who wins the majority of Missouri delegates.

Accounting for Intersections

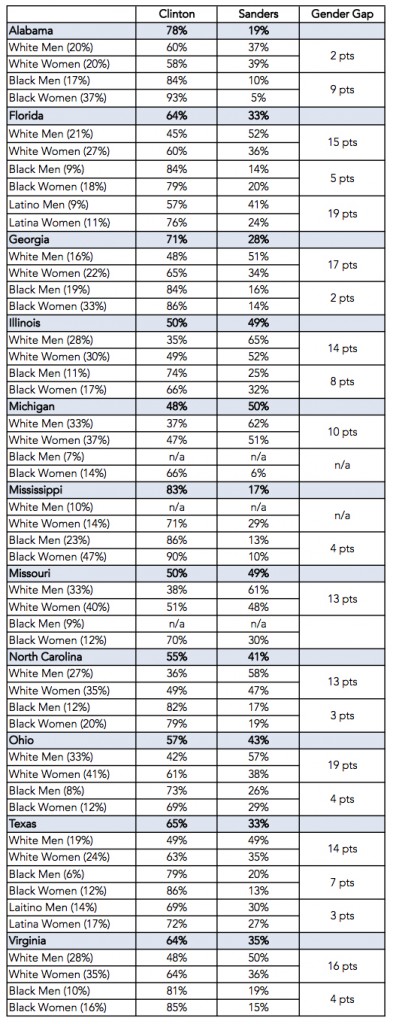

As I’ve written recently, black women have been essential to Clinton’s firewall, supporting her in the greatest numbers among all women. While there are gender gaps among black voters across Democratic contests, they are smaller, on average, than the gender gaps among white Democrats in contests thus far (where polling by race and gender is available). In fact, Sanders won the majority of white men in eight of ten states where data is available; in a ninth state, Clinton and Sanders tied among white male Democrats. Sanders lost to Clinton among white men in Alabama, where 78% of all Democrats supported Clinton. (While data are unavailable, it’s very likely that he lost among white men in Mississippi as well, where 83% Democrats voted for Clinton.)

Up until this week, Clinton had done better among black women than in any other race and gender subgroup (where data were reported), including black men. Interestingly, this week, she continued to dominate among black voters, but by slightly smaller margins in Midwest states. The gender gap also varied in direction in the three states with data available this week; black men supported Clinton by slightly larger margins than black women in North Carolina, Ohio, and Illinois.

The only other sub-breaks of data available in publicly-released exit polls are by gender and marital status, and again only (consistently) in Democratic contests. The gender gap among unmarried voters is most interesting, especially due to Sanders’ significant support overall with this segment of (often younger) voters. Where data on both unmarried men and women’s votes is available, Clinton wins more unmarried women than men. In Massachusetts, she won among unmarried women (53%), while Sanders dominated among unmarried men (69%), yielding a 23-point gender gap between unmarried men and unmarried women for both Democratic candidates. Unmarried women were estimated to be about 26% of the Massachusetts Democratic primary electorate, however, compared to 18% for unmarried men. Just this week, Clinton won the majority of unmarried women voters in three of five primary contests, while Sanders won the majority of unmarried men. Gender gaps among unmarried voters were 23 points in Florida, 16 points in Ohio, and 15 points in North Carolina. In Illinois, Sanders won the majority of unmarried men and women, but with a seven-point gender gap where unmarried women were still more likely than unmarried men to support Clinton.

Stay Tuned

We will continue to update these data as states cast their votes for our next president. Stay tuned for new data and analyses of the gender gap in primary contests. In the meantime, monitor the gender gap in presidential polling on our website at this link.