Black women in criminal justice positions have recently received a great deal of attention. We can look to the historic elections of a number of Black women judges and prosecutors in the 2018 cycle as one example. We can also look to media coverage of Letitia James, New York Attorney General, and Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis. Both women brought charges against former President Trump. Like previous Black women in these positions – James and Willis have not shied away from bringing charges in tough cases.

Despite this media attention, Black women are severely underrepresented in office as judges and prosecutors. In fact, judges and prosecutors are overwhelmingly white and male. This is consequential because there is evidence (at least on the part of judges) that the identity of a judge and the mere presence of more diverse judges can impact case outcomes (Harris 2018; Moyer 2013; Haire and Moyer 2015). Moreover, there is some evidence that running for judicial office represents less of an ambition barrier for women of color (Jensen and Martinek 2009), but it is not clear if those same dynamics exist for prosecutorial office or how this lowered ambition barrier applies to Black women in particular. Altogether, this lack of diversity amongst judicial and prosecutorial elected officials brings into question whether the problem lies in a lack of diverse candidates running for these positions or in voters being unwilling to vote for diverse candidates.

This brief focuses on how voters perceive Black women (and their race-gender counterparts) as judges and prosecutors for elected office. Ultimately, I find that respondents do not perceive Black women distinctly from their race-gender counterparts across a myriad of descriptive traits nor are Black women disadvantaged in election scenarios. This is good news for Black women who are considering running for judicial or prosecutorial office as voters are just as willing to support a Black woman for these electoral positions as a candidate of another race-gender identity. These results suggest that more attention should be paid to understanding Black women’s motivations and deterrents to running for criminal justice elected positions.

How did I do my research?

In order to understand how the public perceives diverse candidates, particularly Black women, running for judicial and prosecutorial office, I conducted two experiments.

Examining Traits

In the first experiment, respondents are asked to evaluate the traits they associate with different groups of judges and prosecutors who vary by race and gender. Here, I examine traits the public associates with Black women judges and prosecutors (in comparison to their race-gender counterparts). Respondents were randomly assigned a trait (like self-centered, competent, and dependable). The prompt read: “How frequently do you think that people in general would use the term [attribute] to describe [demographic group of judges or prosecutors]?” Respondents were asked to evaluate how often that characteristic would be applied to a group (Black women, Black men, white men, white women, men [no race specified], and women [no race specified] judges or prosecutors).[1] I use these evaluations to model how similar or dissimilar respondents believe Black women prosecutors and judges are perceived in relation to their race-gender counterparts.[2]

At the most basic level, the traits we associate with groups (stereotypes) are the heuristics we use to sort or categorize in-groups and out-groups (Tajfel and Turner 1971; Tajfel and Turner 2004). More often than not though, these categories develop meaning in such a way that we not only are able to distinguish between groups, but we come to understand what is perceived as “good” or “bad” and who is considered to be the “top” or “bottom” of the social hierarchy (see Omi and Winant 2014; Hills Collins 1991; Zou and Cheryan, 2017). In addition, these categories have both political and social meaning, especially as it relates to Black women (see Collins, 2002; Sewell, 2013; Harris-Perry, 2011; King, 1973; Jordan-Zachery, 2017). However, much of the work that has examined how Black women are perceived has not examined elites (although see Carew 2012, 2016).

Examining Vote Choice

While understanding how respondents might apply stereotypes to Black women judges and prosecutors is an important part of the story about how potential voters might evaluate them on the campaign trail, it is not the whole story. It is also meaningful to capture willingness to choose a Black woman (in comparison to their counterparts) when it comes to election scenarios. In order to capture the dynamic nature of campaigns, how Black women show up on the campaign trail, and the various opponents they may face, I use a conjoint analysis to examine vote choice in my second experiment.

In the experiment, respondents were presented with six hypothetical pairs of candidates. A conjoint design allows respondents to evaluate two hypothetical candidates, but also randomly varies the features or attributes that are associated with each candidate (see Hainmueller et. al 2014). The pairs of candidates were presented in a table in which the randomized characteristics of each of the candidates were listed. For each pair of candidates, respondents were asked to imagine the candidates are running against one another in an election for a prosecutorial or judicial position.

For the judicial election scenario, I vary the race and gender of the candidates, along with the institution at which they received their legal education, previous office and a rating from the American Bar Association for suitably in judicial office. For the prosecutorial election scenario, I vary the race and gender of the candidates, along with the institution at which they received their legal education, previous office, and the candidate’s approach or philosophy about the position. After being presented with each profile, respondents were asked to evaluate the candidates and decide which one they would vote for as well as how they would evaluate each candidate on a 0 to 100 thermometer. The repeated nature of the experimental task allows for the evaluation of preferences associated with features or attributes associated with each candidate. I also take into account how the race and gender identity of the respondents might influence their preferences.

Results

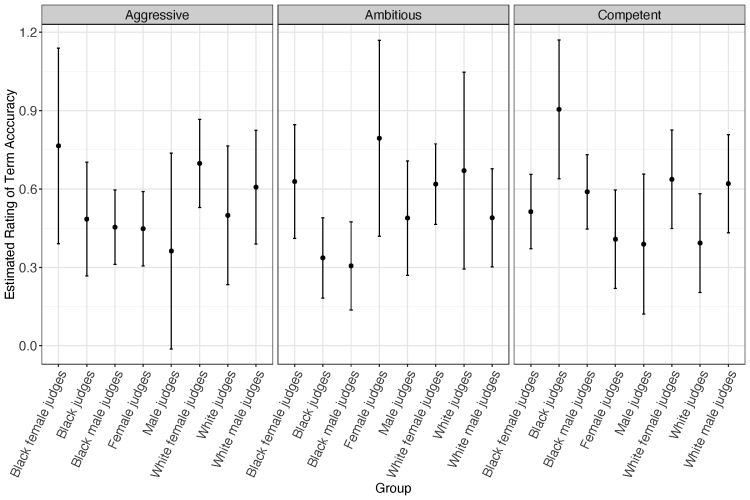

I found no significant difference between how Black women judges were evaluated on 36 different traits than Black judges, Black male judges, female judges, male judges, white female judges, white judges, and white male judges. I show examples of this in the data below - which reflects respondents’ perceptions of how accurately traits – like being aggressive, ambitious, or competent – applies to a judge in a race-gender group. While there are some differences, these differences are not large enough to suggest Black women judges are evaluated in ways significantly different than those judges with different race and gender identities. This is important to note for Black women who are considering judicial office as it suggests that potential voters do not count Black women out for this position or perceive Black women in a way that hurts their electoral prospects. Black women judges are just as competent as their counterparts of other race-gender identities and the evidence suggests that respondents see this.

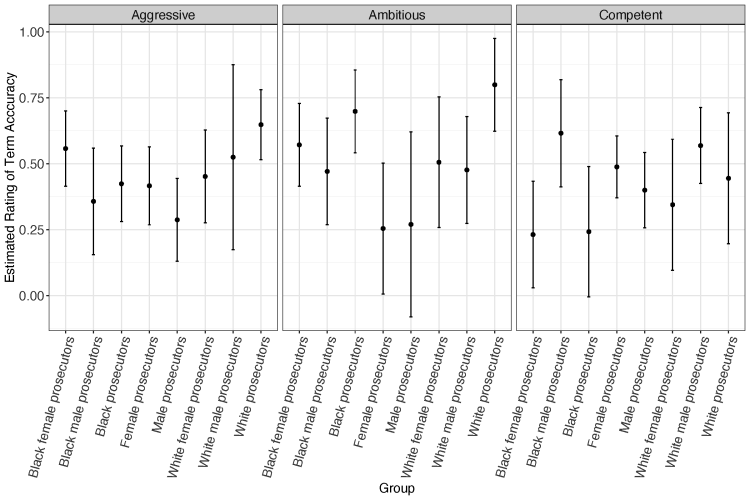

A similar story emerges for prosecutors. I found no significant difference between how Black women prosecutors were evaluated on 36 different traits than Black prosecutors, Black male prosecutors, female prosecutors, male prosecutors, white female prosecutors, white prosecutors, and white male prosecutors. I show examples of this in the data below, again with a focus on three traits – aggressive, ambitious, and competent. Just as with judges, there is variation in how much respondents believe these traits apply to a race-gender group, but these differences are not large enough to suggest that Black women prosecutors are perceived significantly different from their race-gender counterparts. Just as with Black women considering judicial office, these results bode well for Black women who are considering elected prosecutorial positions, like states’ attorney or state prosecutor. Respondents perceive Black women prosecutors just as they perceive prosecutors from other race-gender groups, which is evidence that Black women are not at a disadvantage when seeking elected prosecutorial office.

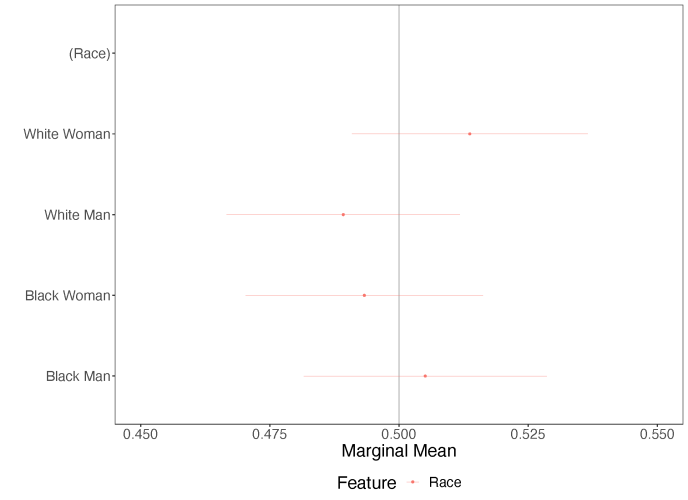

While the evidence about traits associated with judges and prosecutors is suggestive, we might consider how Black women fare in an actual vote choice scenario. Below, I focus on respondents’ preference for a judicial candidate based on the candidate’s race and gender identity.[3] The evidence makes clear that a candidate being a Black woman does not increase or decrease a respondent’s willingness to vote for that candidate. We see a similar effect across race-gender identity. Respondents are just as likely to choose a Black woman candidate for judicial office as any other candidate. This is evidence that Black women are not penalized for their identity and potential voters are willing to select a Black woman as their preferred judicial candidate. For potential candidates, this is telling evidence about their chances to win when they run.

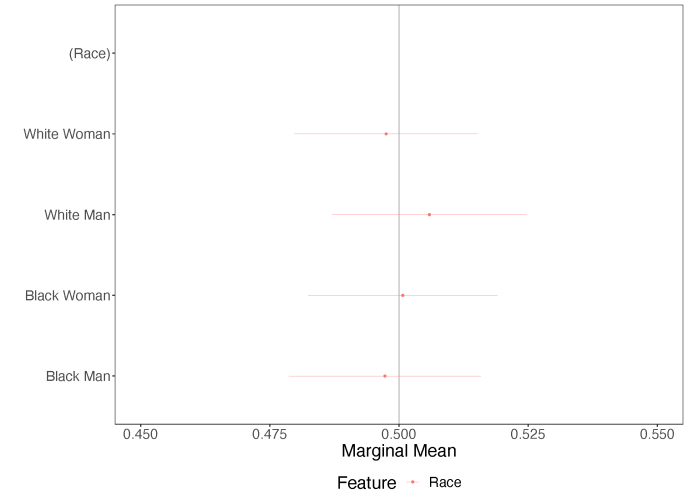

Below, we see a similar narrative emerges for prosecutorial vote choice. Again, I focus on respondents’ preference for a candidate based on the candidate’s race and gender identity. A candidate being a Black woman does not significantly increase or decrease candidate favorability. Other race-gender identities also do not significantly increase or decrease preference for a candidate. Respondents were just as likely to select a Black woman as their preferred candidate as any other candidate. Thus, the evidence suggests that Black women’s identity is not a factor in how respondents are making their vote choice for prosecutorial candidates. This is further evidence that there is an opportunity for Black women’s electoral success in criminal justice positions.

Implications

Altogether, the evidence here suggests that Black women are not disadvantaged or advantaged in how they are perceived as judges and prosecutors or in vote choice for judicial and prosecutorial seats. In particular, Black women judges and prosecutors are not perceived distinctly from their race-gender counterparts who also hold these positions on traits like aggression, ambition, and competence. Looking to vote choice, there is neither a significant preference for nor aversion to Black women candidates. This leaves room for Black women to showcase their issue positions and other attributes that might encourage voters to show up for Black women candidates on election day.

Both sets of findings seem to suggest that there is a political opportunity for Black women to run for judicial and prosecutorial seats. More recent elections of Black women in judicial and prosecutorial seats in states like Maryland, Illinois, Georgia, Texas, and New York speak to the fact that Black women can do well electorally in these positions. Practitioners should be mindful of encouraging more Black women to seek elected positions beyond legislative seats. There is indeed an opportunity for Black women to run for and win these criminal justice positions.

Suggested Citation: Scott, Jamil. 2023. “Running for Justice? Understanding Black Women Judicial and Prosecutorial Candidates” Center for American Women and Politics, Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ.

[1] Additional traits to which respondents could be exposed include: happy, talkative, warm, friendly, law-abiding, attractive, sincere, innocent, trustworthy, nurturing, kind, passive, self-centered, emotional, hostile, inconsiderate, sexually promiscuous, vain, aggressive, violent, boastful, complaining, ambitious, competent, dependable, smart with everyday things, determined to succeed, hardworking, confused, dependent, dirty, illogical, impulsive, incoherent, gullible, superstitious, undisciplined, lazy and irresponsible. Previous work has used terms like these to examine how the public might apply stereotypes to Black and female politicians, respectively (see Schneider and Bos 2011,2013).

[2] I use a linear mixed model to examine how respondents relate the race and gender of prosecutors and judges (respectively) to traits. Because respondents are not asked about how each trait is related to a particular race-gender group, I use the predicted values from the linear mixed model to show where there might be significant differences in the predicted probabilities.

[3] I note that the results below are from a conjoint analysis. I display the marginal means associated with randomized candidate identities shown to respondents. The horizontal line (at 0.50) in the figure tells whether or not the marginal mean is significant. While the conventional wisdom is to display the average marginal component effect, the estimate for a particular attribute can vary by the chosen baseline level for the attribute. In order to understand the favorability of a given feature, regardless of reference group, I present the estimated marginal means.