In recent years, Black women have been entering in elective offices at historic rates. For example, 28 Black women currently serve in the U.S. Congress — the highest number of Black women in Congress to date. More recently, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson became the first Black woman to be confirmed to the U.S. Supreme Court. And Kamala Harris has also broken barriers at the highest levels of U.S. politics — as the nation’s first Black woman to serve as vice president. In short, Black women are changing the American political landscape in remarkable ways — entering into elected and appointed positions where they have historically not been represented.

As Black women continue to rise to political prominence, this study seeks to establish the extent to which they face unique penalties among the American public on account of their intersectional race-gender identity. Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989) famously coined the term “intersectionality,” which describes how social identities such as race, class, and gender intersect to create distinct realities for individuals and groups. The intersectionality framework (Crenshaw 1989, 1991) points to the plausible expectation that Black women political elites will face unique penalties, in terms of perceived personality traits and abilities and electoral support, relative to their race-gender counterparts (e.g. white women, white men, and Black men). Furthermore, in this study I test the applicability of the intersectionality framework to understanding whether Black women’s dual race-gender identity puts them at a heightened disadvantage among the American public, relative to their counterparts of other race-gender groups. In short, I ask the following question: are Black women political elites evaluated more negatively by the American public compared to their counterparts of other race-gender groups?

Through a national survey, I find:

- The combination of racial resentment and modern sexism has a particularly powerful influence on the extent to which respondents characterize Black women political leaders as angry/aggressive, demonstrating that Black women political figures are disadvantaged in this context on account of their intersectional identity.

- On its own, racial resentment exerts a powerful impact on respondent attitudes toward the political figures in this study, even more so than modern sexism. It is clear that respondents who have high levels of racial resentment are not only likely to penalize the Black political figures in the study, but all four of the race-gender groups analyzed (Black women, Black men, white women, and white men).

- Black women are not distinctly disadvantaged from political figures in different Black and white race-gender groups in respondent evaluations that they are strong leaders or “care about people like me.”

- These findings for the Democratic political leaders evaluated in this study hold across respondents of different party identifications, suggesting that the distinct bias toward Black women leaders persists among both Democrats and Republicans.

Data and Methods

In January 2022, I conducted a survey with Cloud Research (Prime Panels), utilizing a nationally-diverse sample of the U.S. population across factors such as age, race, gender, and partisanship. In total, there were 1,103 respondents. In the survey, respondents were exposed to a brief biography and headshot of the following twelve political figures before answering questions pertaining to their characteristics: Kamala Harris, Joe Biden, Nancy Pelosi, Jim Clyburn, Maxine Waters, Hakeem Jeffries, Carolyn Maloney, Jim Himes, Marcia Fudge, Pete Buttigieg, Lloyd Austin, and Janet Yellen. Note here that all the political figures that respondents were exposed to are Democrats or Democratic appointees and identify as Black or white.[i] Respondents were then prompted to answer a series of questions evaluating the traits of these political figures. For each political figure, they were asked the following: “Please indicate how well you believe each of the following statements describe [insert political figure name].” On a five-point scale from “not well at all” to “extremely well,” they indicated the extent to which each political figure provides “strong leadership,” “really cares about people like me,” and “is generally angry/aggressive.”

In addition to providing perceptions of these political figures, survey respondents answered questions that are used to determine alignment with modern sexism and racial resentment.[ii] Existing literature on racial resentment and modern sexism (Karpowitz et al. 2021; Ratliff et al. 2019; Knuckey 2019; Highton 2004; Swim and Cohen 1997; Reeves 1997; Yoder and McDonald 1997; Moskowitz and Stroh 1994; Terkildsen 1993) suggests that respondents who score high on both scales will hold less favorable evaluations of Black women political elites than those who do not. Furthermore, this study takes a specific focus on understanding respondent evaluations of Black women political figures from the perspective of those who score high on racial resentment and modern sexism, simultaneously.

In order to examine whether the combination of racial resentment and modern sexism produces a significant influence on respondent attitudes toward Black women political elites, I grouped respondents into four primary categories:

- Low on modern sexism and low on racial resentment (N = 392)

- High on modern sexism and low on racial resentment (N = 149)

- Low on modern sexism and high on racial resentment (N = 217)

- High on modern sexism and high on racial resentment (N = 345)

Results

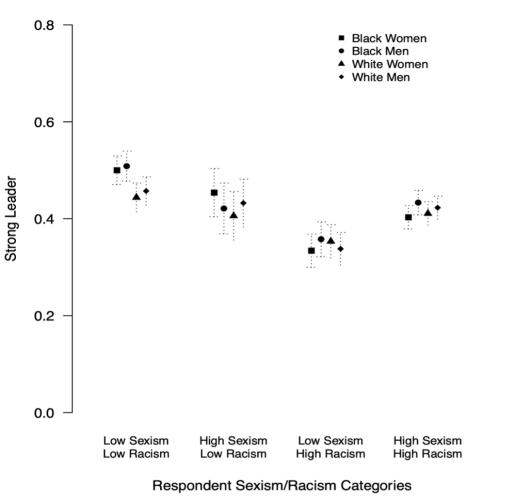

In order to test whether respondents’ scores on racial resentment and modern sexism produce a significant influence on perceptions toward Black women political elites, I start by examining the relationship between respondent evaluations of “strong leadership” and their levels of sexism and racial resentment. First, racial resentment has a particularly powerful impact on respondent attitudes in the “strong leader” characteristic toward all the political figures, regardless of race or gender. As respondents move from being low in racial resentment to high in racial resentment, all political figures experience decreased evaluations of the strength of their leadership. While Black women do experience decreased evaluations as respondents move from low in racism to high in racism, all their race-gender counterpart groups also experience this effect.

Respondent Evaluations of “Strong Leader” Characteristic

According to Modern Sexism and Racial Resentment

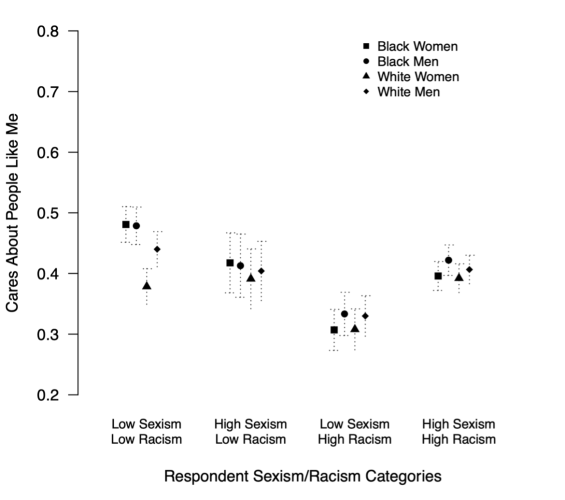

Next, I examine respondent attitudes toward Black women political figures according to the “cares about people like me” characteristic. There is no indication that respondents (particularly those who score high on modern sexism and high on racial resentment) are less likely to perceive Black women as possessing the “cares about people like me” trait relative to all three of their race-gender counterpart groups. And, once again, all the political figures receive the lowest evaluations in the low sexism/high racism category as opposed to the high sexism/high racism category.

Respondent Evaluations of “Cares About People Like Me” Characteristic

According to Modern Sexism and Racial Resentment

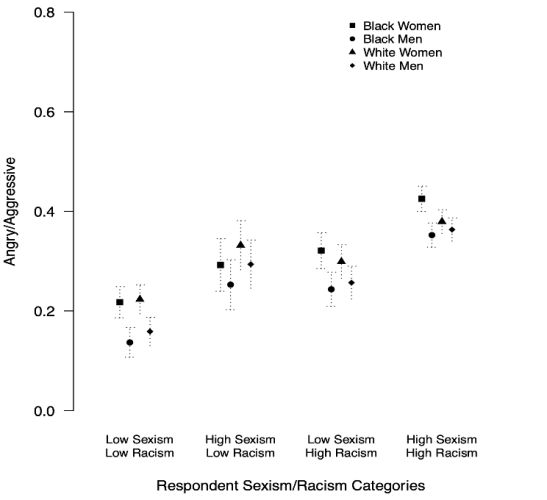

Last, I turn toward an examination of respondent evaluations toward Black women political figures according to the “angry/aggressive” characteristic. There is a salient and significant finding here among respondents in the high on racism/ high on sexism category: relative to all three of their race-gender counterpart groups, Black women political figures here are perceived to be more angry/aggressive relative to respondents who score low on racism/low on sexism. This is a key finding to emerge from this study — one that should not be taken lightly: when combined, racial resentment and modern sexism have a particularly powerful influence on the extent to which respondents associate Black women political leaders with negative characteristics. This finding aligns with previous work on the perpetuation of historical stereotypical tropes surrounding Black women (e.g., Harris-Perry 2011l). This finding also indicates that Black men are the least likely to be evaluated as angry/aggressive in each of these categories, demonstrating that Black women political figures are disadvantaged in this context on account of their intersectional identity when respondents in the high racism/high sexism category are compared to those in the low racism/low sexism category.

Respondent Evaluations of “Angry/Aggressive” Characteristic

According to Modern Sexism and Racial Resentment

Implications

This research is critical for a number of reasons. There is so limited empirical information surrounding the experiences of Black women political leaders that it is imperative that scholars of race and gender politics continue to advance this work and ascertain whether minority group members are disadvantaged due to their intersecting identities. This is particularly important as the American political arena continues to grow more diverse across race and gender lines than ever before. Black women in America have a long history of disadvantage, yet they have continued to rise to political prominence in recent years. As Black women continue to seek high level elective and appointive offices, it is prudent to study and understand the extent to which their intersectional identity impedes (or does not) their progress in the political arena. Further, the findings of this study have implications both for Black women’s ability to get elected, or appointed, as well as the factors that affect their success once in office. In short, if Black women are penalized in the political arena, then this undermines the descriptive and potentially the substantive representativeness of our government.

More importantly however, the findings here (particularly the findings surrounding perceptions of anger and aggressiveness) indicate a need for political practitioners nationwide to rethink how historical tropes continue to inhibit those with marginalized, intersecting identities. As more Black women continue to enter into the political limelight, it is critical that practitioners, government officials, and the media are aware of the ways in which troubling and outdated stereotypes have the potential to undermine the success of Black women candidates. It is therefore important, perhaps now more than ever, for organizations dedicated to addressing race and gender-based prejudices to continue to work toward educating voters nationwide about the ways in which conscious and unconscious biases play an important role in perceptions toward Black women political figures. Moreover, we can all do our part in confronting these stereotypes by rejecting these ideals that only serve to mislabel and diminish the efforts of Black women — who represent a vital aspect of the American political system.

Sydney L. Carr is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at College of the Holy Cross.

Suggested Citation: Carr, Sydney L. 2023. "Understanding Public Opinion Toward Black Women Political Elites." Center for American Women and Politics, Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ.

References

Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. "Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color." Stanford Law Review 43: 1241.

Crenshaw, K. 1989. "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics." University of Chicago Legal Forum 1: 139-167.

Harris-Perry, Melissa V. 2011. Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America. Yale University Press.

Highton, Benjamin. 2004. "White Voters and African American Candidates for Congress." Political Behavior 26: 1-25.

Karpowitz, Christopher F., Tyson King-Meadows, J. Quin Monson, and Jeremy C. Pope. 2021. "What Leads Racially Resentful Voters to Choose Black Candidates?." The Journal of Politics 83.

Knuckey, Jonathan. 2019. “'I Just Don't Think She Has a Presidential Look': Sexism and Vote Choice in the 2016 Election." Social Science Quarterly 100(1): 342-358.

Moskowitz, David, and Stroh, Patrick. 1994. "Psychological Sources of Electoral Racism." Political Psychology 15: 307.

Ratliff, Kate A., Liz Redford, John Conway, and Colin Tucker Smith. 2019. "Engendering Support: Hostile Sexism Predicts Voting for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton in the 2016 US Presidential Election." Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 22(4): 578-593.

Reeves, Keith. 1997. Voting Hopes or Fears?: White Voters, Black Candidates & Racial Politics in America. Oxford University Press on Demand.

Swim, Janet K., and Laurie L. Cohen. 1997. "Overt, Covert, and Subtle Sexism: A Comparison Between the Attitudes toward Women and Modern Sexism Scales." Psychology of Women Quarterly 21(1): 103-118.

Terkildsen, Nayda. 1993. "When White Voters Evaluate Black Candidates: The Processing Implications of Candidate Skin Color, Prejudice, and Self-Monitoring." American Journal of Political Science: 1032-1053.

Yoder, Janice D. and Theodore W. McDonald. 1997. "The Generalizability and Construct Validity of the Modern Sexism Scale: Some Cautionary Notes." Sex Roles 36: 655-663.

[i] I only include Democrats because there are so few Black female (and Black male) Republican elected officials nationwide.

[ii] The racial resentment scale is comprised of four questions. The question wording is as follows (responses are captured using a five-point scale, ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree):

- “Irish, Italian, and Jewish ethnicities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same without any special favors.”

- “Generations of slavery and discrimination have created conditions that make it difficult for blacks to work their way out of the lower class.”

- “Over the past few years, Blacks have gotten less than they deserve.”

- “It's really a matter of some people just not trying hard enough: if Blacks would only try harder they could be just as well off as whites.”

The modern sexism scale is comprised of eight questions. The question wording is as follows (again, responses are captured using a five-point scale, ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree):

- “Discrimination against women is no longer a problem in the United States.”

- “Women often miss out on good jobs due to sexual discrimination.”

- “It is rare to see women treated in a sexist manner on television.”

- “On average, people in our society treat husbands and wives equally.”

- “Society has reached the point where women and men have equal opportunities for achievement.”

- “It is easy to understand the anger of women’s groups in America.”

- “It is easy to understand why women’s groups are still concerned about societal limitations of women’s opportunities.”

- “Over the past few years, the government and the news media have been showing more concern about the treatment of women than is warranted by women’s actual experiences.”